While it may not seem like there is much to forage in the desert, there are quite a few edible and medicinal plants that have been used throughout history! Learn about Sonoran Desert foraging and what is available in the summer in this sparse but beautiful desert region.

Want to save this post for later?

Wildcrafting Weeds

If you want to learn more about the edible and medicinal weeds that surround us and how to use them, check out my eBook: Wildcrafting Weeds: 20 Easy to Forage Edible and Medicinal Plants (that might be growing in your backyard)!

Foraging in the Desert

Dry barren land with cacti baking in the sun, bushes that seem to have been mummified beneath dust, and a lone tumbleweed being swept in a searing breeze are typically what come to mind when envisioning a desert landscape.

While at first glance the Sonoran Desert may strike you as having a scarcity of resources, on closer inspection you’ll uncover an abundance of edible and medicinal plants that have been used by the Tohono O’odham Native American tribe for as long as they’ve resided there.

Thousands of years ago, their predecessors, the Hohokam, were masters of desert dwelling and gathered all of the wild plants that I’m going to share with you today.

Sonoran Desert Foraging Considerations & Ethics

It’s important to note that some of the plants contained in this post are protected from vandalism, theft, and unnecessary destruction by Arizona’s Native Plant Law.

Mesquite, ironwood, palo verde, and saguaro are unique to the Sonoran Desert bioregion and cannot be removed or relocated from state or federal land.

On private property, only with written permission and a permit from the Arizona Department of Agriculture can you relocated these native plants. Most desert plants fall somewhere under this law, including all cacti and various smaller plants.

Before you start harvesting, look over Arizona’s list of protected native plants and take the appropriate steps to ensure you’re foraging responsibly and within the law!

The Sonoran Desert: A Wet & Dry Summer

The Sonoran Desert consists of five seasons with summer being split into two: dry (May, June) and wet (late June, July, August, September).

The dry and hot weather of early summer gives way to life restoring monsoon rains that soak the region during this time.

The Tohono O’odham considered this as the beginning of the new year and was cause for celebration.

Desert Foraging During Dry Summer

Mesquite Tree

There are three mesquite trees native to the Sonoran Desert:

- Velvet, Prosopis velutina

- Screwbean, Prosopis pubescens

- Honey, Prosopis glandulosa

Mesquite is easy to identify and all three varieties are edible, however, velvet mesquite is considered to produce the sweetest and most abundant legume pods in the hot, dry months of summer.

Velvet mesquite is found throughout Arizona in washes, bottom lands, and drier slopes up to 4,500′ in elevation. Depending on water conditions, it can grow into a large shrub or small tree. Unlike most of the other members of the pea family that are edible, it’s the pod and not the seed that is considered choice.

While foraging, it’s a good idea to wear gloves, as spines cover the young branches of the mesquite tree!

In late spring and early summer, gather the leaves when they’re fully mature and catch the clearish sap by placing a pan under any of the tree’s wounds. Any hardened sap, may also be gathered for later use.

By mid to late summer, it’s time to gather the tan pods that are still attached to the tree.

After these mesquite pods become dry, and brittle are they ready to take their tastiest form, a coarse gluten free flour made by grinding the seed and pod. Native desert dwellers wore deep mortar holes into solid rock while grinding the pods, evidence of just how long and deep their connection with the mesquite tree extends.

Depending on the species, the flour ranges from sweet to bland and can be used as a baking base combined with other flours. Use the flour to make high protein, gluten free cookies, mesquite and wheat sourdough bread, or mesquite tortillas!

The pods can also be boiled down into a sweet mesquite bean syrup that would make a delightful addition to gluten free pancakes, if you’re looking to get the full mesquite experience in one dish.

In addition to being edible, all parts of the mesquite tree have medicinal benefits. The pods aid in stabilizing blood sugar levels, are protein rich, and have been found to help lower glycemic responses.

Mesquite leaf powder can also be applied to scrapes and cuts to lessen inflammation and stop minor bleeding. The clear sap nodules can be sucked on straight from the tree as a sweet treat that also has the ability to relieve heartburn.

A tea made from a blend of the clear sap and inner red bark can aid sore throats and a brew of leaves relieves stomach aches. When applied topically to the skin, mesquite leaf tea helps soothe sunburn, insect bites, and rashes.

What’s more, this giving tree not only supplied natives with an important food source, but was an essential resource in tool making. The bark was used to make baskets and fabric. The wood, in building and fire making.

Ironwood Tree

Ironwood trees, Olneya tesota, can be identified easily by their gray ghost-like bark, pink or purplish flowers, and small green leaves. They’re also one of the desert’s tallest trees at 35′ tall.

Like mesquite, sharp spines exist on branches, so be cautious while harvesting seed pods. Growing in low elevations up to 3500′, ironwood loves frost-protected habitats such as: basins, valleys, drainages, or washes.

All native tribes in the Sonoran Desert relied on the ironwood’s protein-rich seeds during the hot, pre-monsoon months as a necessary food source. Early in the dry summer months of May and June, immature green seed pods can be harvested.

To store for later use, a quick blanch of the beige pods before freezing will do the trick. When you’re ready to use them, steam or boil for fifteen or thirty minutes, as they can still be fairly bitter at this time. Alternatively, you can dry them fully for storage, or grind into a gluten free flour for baked goods.

Later in the season, while the pods are still green, the mild, pea flavored seeds can be harvested from the tree and eaten raw in salads, salsas, or cooked like sweet peas. Because they’re high in phytates, high quantities shouldn’t be eaten raw.

Mature, brown, dry seeds turn hard in their pods during the wet summer in late June through August. Seeds removed from their pods store well and can be used long after the season is over. Try soaking and sprouting them at this stage like you would a mung bean to break down their phytic acid and improve digestibility.

Native desert people prized ironwood for its dense wood and used it in their creation of bows and handles. They frequently gathered it firewood and was ideal four building, due to its resistance to rot and fire.

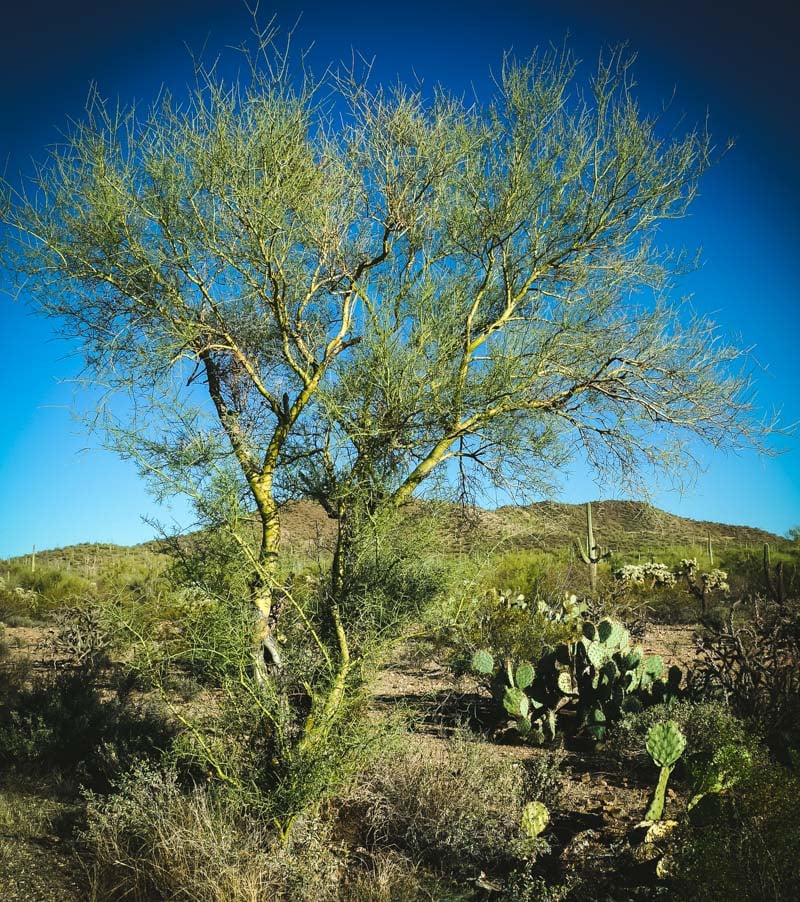

Palo Verde Tree

Two species of this legume bearing tree reside in the Sonoran Desert:

- blue palo verde, Parkinsonia florida

- foothills palo verde, Parkinsonia microphylla

Both can often be found growing among ironwood and saguaro in low elevation flats, rocky hillsides, and foothills.

Palo verde is extremely easy to identify with its distinctive green bark and bright yellow edible flowers that start blooming mid-April through May. The flowers have a pea-like flavor and can be slightly sweet, especially from foothills palo verde trees. Use them raw in salads, cocktails, or munch on some during a desert hike!

Soon after the flowers are pollinated by birds and bees, green seeds develop in their pods during the dry summer months of mid May through June. At this time, remove the pods and eat the bright green seeds found inside.

Blue palo verde seeds can be a bit bitter and may require multiple soaking and rinsing cycles to remove the poor taste. To store, blanch the pods, remove the seeds, and freeze for later use. You can also remove the seeds from the pods, and dehydrate them for use in the winter months.

Like the other legume trees I’ve mentioned above, the pods may also be removed from the tree once they’re dry, brittle, and brown right before the start of wet summer. These dry, ripe seeds can be soaked and simmered like any dried bean. Roasting and grinding into a gluten free flour is another great use for the pleasant tasting seeds!

Unlike mesquite and ironwood, palo verde is not valued as firewood and is more irritant than other woodsmokes.

Saguaro Cactus

Saguaro, Carnegiea gigantea, can be found only in the Sonoran Desert areas of central/southern Arizona and southeastern California. It’s one of the largest columnar cacti in the world!

I love that the other common name for this Sonoran Desert native is “giant cactus”, as that’s all you really need to know when identifying it.

It probably goes without saying, but let me remind you, cacti have small thorns or glochids that can range from mildly irritating to painful. Be cautious of your surroundings out in the field, especially since you’ll be in rattlesnake habitat!

In May, saguaro cacti bloom brilliant white flowers (Arizona’s state flower) followed by large, sweet, delicious fruit with flavor and texture akin to that of fig. Many desert foragers consider saguaro to have the best tasting fruit of all Sonoran Desert cacti and I think they’re right!

The fruit ripens and is gathered during the dry summer months of June through early July. This fruit harvesting is an indicator that the much needed monsoon season will soon be arriving and the desert will be returning back to life.

Before you start gathering, remember that saguaro cacti are protected on Arizona publicly owned land. You should contact the government office that manages the land you wish to forage on to inquire about their regulations on collection of fruit, as there are many areas where you cannot. On private land, make sure you have permission first!

After getting the go ahead, Use a long stick or an old saguaro rib to dislodge ripe fruit from the cactus’ arms and trunk. Gather up your treasure, split them in half, and behold the bright red, seedy flesh that can be eaten raw, turned into jams, jellies, syrups, ice cream, or wine.

When dried, it also makes a great fruit jerky! This nutritious fruit is packed with antioxidants and anti-inflammatory properties. The black, tiny, crunchy seeds rich in protein and fat, pair perfectly with the sweetness of the fruit’s flesh.

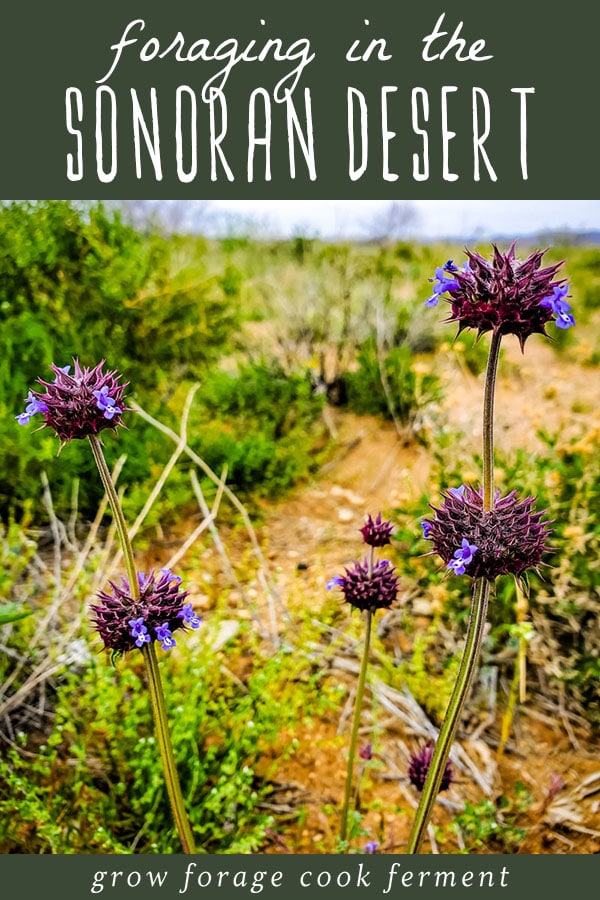

Desert Chia

I’m sure at one time or another, you’ve added chia seeds to yogurt or drank beverages with those mucilaginous pea-sized globs in it. Desert chia, Salvia columbariae, is the plant they come from! They’re commonly found along roadways, rocky hillsides, and love areas with disturbed soil.

In early March and April, single stalks shoot up with flowers growing in ring-like clusters. These blue-purple flowers are edible and pleasant tasting. Each flower contains a chia seed after pollination and in May or June they turn gray or brown.

At this point, the entire plant dies, the cluster of flowers dry, and seed pods open before being dispersed by the wind. Make sure to wear gloves when harvesting, the seed pods can be sharp. Crush the pods over a container to collect the seeds contained inside.

This powerful plant ally is high in fiber, protein, omega-3s, calcium, and iron. During the dry summer months, it was prized by many native tribes for its hydrating properties that slow digestion and absorption of starches.

Today, use desert chia seeds the same way you’d use store bought chia, which have nearly identical nutritional aspects. I like to add them into pudding and jam as a natural and nutritious thickener!

A tincture or tea made from the leaf, can be used to ease indigestion, gas, and bloating. In winter, try gargling cooled tea to bring relief to sore throats.

Desert Foraging During Wet Summer

Prickly Pear Cactus

Perhaps the most recognizable and widely used desert plant, the prickly pear cactus. Opuntia engelmannii and Opuntia phaeacantha are abundant in the Sonoran Desert bioregion, but there are at least eighteen species total, some of which are hybrids.

This hydrating plant can be found thriving on hillsides, lower desert basins, and canyon bottoms. The prickly pear cactus is made up of green, connected, pancake-like pads that arise from a thickened base.

Esteemed for their beautiful, deep magenta, sweet, and seedy fruits that arrive during the humid months of July through September.

The flesh is the ideal choice for eating. But in spring, the new pads that start sprouting up can be eaten too. These tender young pads (nopales) in limited quantities raw or in abundance cooked at this stage. After they age, their insides form fibrous tissue, which can be unpalatable.

Also arriving in spring are bright yellow, edible flower buds. Harvested buds can be pickled, sauteed, stir-fried, whatever suits your fancy! Late spring, whole flowers can be easily removed and their petals can be used for tea or as garnish.

What you don’t want to consume is the spiny, prickly, evil glochids on the flesh of the fruit or the thorns on the pads that can easily plunge into your skin. Eek! I mean, prickly is in the name after all and this cactus does its best to protect its sweet fruits from predators.

It’s a good practice to always wear gloves (and carry tweezers!) while foraging for prickly pears and removing most of the glochids and thorns prior to processing the fruit.

With a pair of tongs, I like to twist the pear from its growth tip and place them in a bowl. They should come off very easily. If you’re struggling to remove a fruit, it’s probably not ripe yet.

After I have a bunch gathered, it’s time to remove the glochids. Use a kitchen blowtorch to burn off any glochids and thorns before carefully rinsing them. Peel off the skin and try making prickly pear gum drops, jelly, a galette, or even these cute prickly pear cupcakes!

You can skip the laborious task of burning them off with a blowtorch if you know you already want to make a prickly pear syrup. It’s much easier removing the glochids by freezing and thawing your fruit before pressing.

By doing this, the fruit breaks down, and the juices are easily released. At this point, carefully strain out the pulp and any glochids. After you have your beautifully colored syrup, try adding it into this Sonoran Desert themed margarita!

Remember I mentioned that you could eat the young paddles? Learn some techniques on how to cook or even pickle them!

Medicinally, the inside of each pad can be applied externally as a poultice to soothe stings, cuts, scrapes, and burns, similar to aloe vera. What’s more, it even has the ability to reduce tissue inflammation and swelling from sprains and contusions!

When consumed, all parts of this healing succulent can lower blood sugar and cholesterol due to its soluble fiber content that slows down sugar uptake. The fruit pulp mucilage mixed with water has a cooling effect that protects the stomach lining and soothes esophageal and stomach irritations, typically caused from acid reflux or heartburn.

Infusions made with the flowers, are high in flavonoids, stimulate the kidney’s excretion of uric acid, and are diuretic.

Devil’s Claw

Two species of devil’s claw call the Sonoran Desert home: Proboscidea althaeifolia, a perennial and Proboscidea parviflora, an annual. The latter is pictured below. Look for it in sandy washes, along roadsides, trails, and any areas with disturbed soils.

Flowers of the annual devil’s claw species bloom pinkish-purple, while the perennial’s are yellow. These clusters of flowers are bell-shaped with five lobes and can often have a purple spot on the upper lip.

Rounded, triangular leaves can have smooth edges or faint teeth. These leaves track the sun each day and droop in the evenings. Sprawling curved stems and fruit are sticky and are enveloped in white hairs.

After the flowers bloom, fuzzy green fruit (that look an awful lot like peppers) start coming up. This plant can smell bad, but don’t let this deter you from foraging for it!

Wearing gloves to avoid stickiness, harvest the fruits in the wet summer months of July and August before they become mature and fibrous. Devil’s claw fruits are pleasant tasting, especially when blanched or peeled to remove any bitterness. Try sauteing, steaming, frying, added to soups and salads.

Try pickling devil’s claw! In the Great Plains region, it was even considered a favorite pickled vegetable and was branded, ‘Pickle of the Plains’ by one entrepreneurial company.

When fully mature, these fruit or seed pods become dry and brown and are no longer edible. At this stage, the long pepper-like tail splits into two horns, reminiscent of a claw. Be careful collecting these dried pods as they can become very sharp. Contained inside are black, edible, and nutritious seeds that are high in protein and fat. Eat them fresh, toasted, or dried.

Wolfberry

Have you ever eaten dried goji berries, Lycium barbarum? Wolfberries are in the same family, just as high in antioxidants as their cousin, and can often be referred to as desert goji. Best of all, you don’t need to go all the way to Asia to forage for them, as they’re local residents in the Sonoran Desert!

Commonly found under ironwood and mesquite trees in exposed flats, hillsides, valleys, and urban landscapes. The thorny thickets in the Lycium family, are similarly formed with their main differences being the shape of the fruits, leaf size, and flower color.

Four species of this perennial bush are commonly found in this area:

- Lycium fremontii, blooms purple flowers with teardrop shaped berries.

- Water jacket wolfberry, Lycium andersonii, have light purple flowers with small, round berries.

- Narrow-leaf wolfberry, Lycium berlanderii, have light purple flowers with small, round berries.

- Pale-leaf wolfberry, Lycium pallidum, bloom light green flowers with a pleasant aroma and big, slightly oval juicy berries. Pale-leaf wolfberries are praised by many wild food foragers as the best tasting.

At the end of winter, these thorn covered bushes transform from playing dead to being covered with pale green, spatula shaped leaves at the start of spring. These branches can be whitish, smooth, and thorny.

Soon after, tubular, bell shaped flowers start to bloom in various colors and hang down. By now, juicy red berries start to appear.

Harvest in spring between March and April. After the summer rains, these plants may fall dormant again, and rebloom and fruit once more before fall. Gather wolfberries during the wet summer months of August and September.

Wolfberries are high in vitamins A and C, and potassium, calcium, and zinc. Try adding wolfberries in place of goji berries in any recipe that calls for them.

These nutrient dense granola bars, raw energy bars, and cashew berry bars all look tasty! You can also blend them up in a berry lime smoothie. Satisfy your sweet tooth with these gorgeous cacao fudge bites or dark chocolate beauty bark!

Combined with Mormon tea, wolfberry makes a potent hay fever reliever that may rival over the counter allergy medicines. Wolfberry may also offer relief to nausea and intestinal spasms. Topically, the leaves can be poulticed and applied to stings, swellings, and contusions.

Well, there you have it, eight edible plants that can be foraged in the Sonoran Desert during the dry and wet summer.

For more information on foraging in desert regions, check out the Desert Harvesters website. They also have an excellent book titled Eat Mesquite and More: A Cookbook for Sonoran Desert Foods and Living if you want to learn more and get some great recipes!

Which of these plants are you most looking for harvesting? If you’re already gathering Sonoran Desert plants already, share with me some of your recipes!

Melody Flynn is an assistant and writer at Grow Forage Cook Ferment. Most of her foraging experience has occurred in the Pacific Northwest, but after spending a year in the Southwest, she has become enamored with desert wild plants.

Can you use desert dandelions to make dandelion wine?

Hi Larae. You could, but I have never tasted them, so I can’t confirm that the flavor would be similar to dandelion wine.

Great article! I was just telling someone how bountiful the Sonora Desert can be and you helped me prove my case. Thank you!

Thanks for the great article. I learned something today, and that makes me so happy!

You’re welcome!

Thank you so much for your article. I’d love to purchase a book or magazine written by you. Very informative

Wow, so much great info! While I’m not in the desert, I still have access to most of these plants and now I know I can use them! I’d love to see more area-specific compilations like this. Keep up the great work, Colleen!